Food of the Gods Book Review/Thoughts

Food of the Gods is one of those books that covers a mix of anthropology, cultural criticism, and psychedelic speculation. McKenna doesn’t pretend he’s playing small, instead he invites us to re-frame human history through our relationship with psychoactive plants. Whether or not you buy every part of the argument, he makes the read worth it.

The book is partly built around what’s often called the “stoned ape theory,” McKenna’s idea that early humans may have experienced accelerated cognitive development through exposure to psychedelic mushrooms. It’s a controversial claim, sure, but McKenna lays it out with enough context and cross-disciplinary references that the premise feels more grounded than people tend to give it credit for. Even if the scientific community hasn’t embraced it as proven fact (because, again, it is not), the theory has conceptual weight — especially if you’re open to the idea that human evolution wasn’t a clean, linear process driven purely by diet and tool use.

Where the book really shines is in how McKenna critiques the way modern society relates to drugs. His framing of contemporary culture as a “dominator state” is sharp, and he makes a compelling case that the substances most socially accepted today — alcohol, caffeine, nicotine — are the ones that keep people productive, compliant, and easy to manage within a larger system. These are the drugs seamlessly woven into capitalism, the ones that fuel long workdays and high stress without questioning the system itself. One may also find it interesting that these drugs have been proven to increase anxiety and stress, both traits of uncertainty that play into keeping the incumbent system in power.

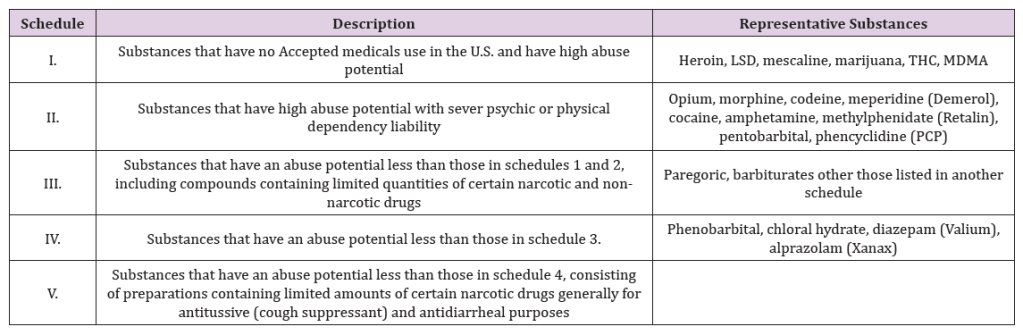

McKenna also examines psychedelics as tools for introspection, healing, and cultural cohesion. His argument isn’t reckless; he emphasizes intention, ritual, and the importance of set and setting. He’s not claiming psychedelics are a one-size-fits-all solution, but pushes back on the idea that they’re inherently dangerous or socially corrosive. In an era where research into psilocybin and related substances is has shown real promise for conditions like addiction, depression, and PTSD, McKenna’s decades-old critiques feel almost prophetic (until you remember that there was a lot of research done before these types of drugs were classified as schedule 1).

Food of the Gods is part history, part polemic, part speculative anthropology — and that’s exactly why it sticks with people (me included). Whether you agree with McKenna entirely or not, he opens doors to conversations that mainstream culture avoided for decades. This book asks you to interrogate your assumptions, rethink the relationship between humanity and consciousness, and question the systems that decide which states of mind are acceptable.

If you’re interested in the intersection of culture, biology, and altered states, this book earns its reputation. Even now, it feels surprisingly current — maybe because the issues McKenna raised are finally catching up to mainstream discussion. It’s not light reading, but it’s the kind that expands the way you think.