The Hidden Forces Warming Our Planet: Understanding Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Every time you flip a light switch, fire up your car, or even open your refrigerator, you’re participating in an invisible but powerful process that’s changing the planet. Welcome to the world of greenhouse gas emissions – a story that’s far more complex than most people realize.

At its most basic level, the greenhouse effect is like wrapping our planet in an ever-suffocating blanket. Solar energy reaches Earth’s surface, but certain gases in our atmosphere act like glass in a greenhouse, allowing sunlight to pass through while trapping heat that would otherwise escape. This process has kept Earth habitable for millions of years, but human activity has thrown this delicate balance completely out of whack.

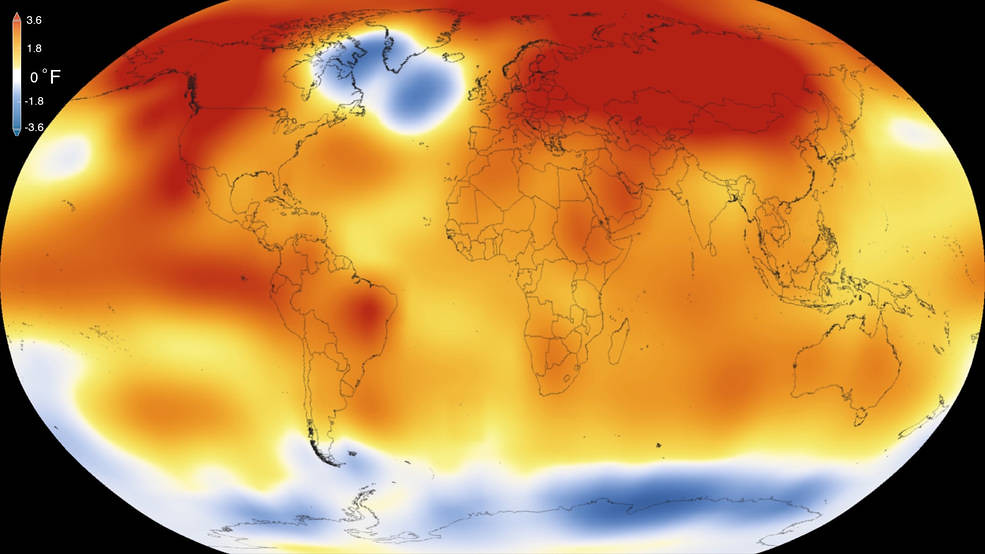

Analyses Reveal Record-Shattering Global Warm Temperatures in 2015 by NASA Goddard Photo and Video is licensed under CC-BY 2.0

The numbers tell a stark story. Global CO₂ emissions from fossil fuels reached a record high of 37.4 billion tonnes in 2024, representing a 0.8% increase from 2023. To put this in perspective, atmospheric CO₂ concentrations reached 422.5 parts per million in 2024 – a staggering 52% higher than pre-industrial levels.

The Big Players in Climate Change

While carbon dioxide dominates headlines as the primary driver of climate change, it accounts for more than half of warming but isn’t acting alone. Methane (CH₄) emissions have almost the same short-term impact as CO₂, despite being released in smaller quantities. What makes methane particularly concerning is its potency – it has a global warming potential 28-36 times greater than CO₂ over a 100-year period.

The sources of methane reveal just how interconnected our modern world is with greenhouse gas emissions. Agriculture is the largest source of anthropogenic methane emissions, closely followed by the energy sector.

But methane isn’t just about burping cows. About one-third of anthropogenic emissions come from gas releases during fossil fuel extraction and delivery, mostly due to gas venting and leaks. Every time we extract natural gas or oil, some inevitably escapes into the atmosphere, creating what experts call “fugitive emissions.” More than 260 billion cubic metres of natural gas is lost annually to venting, leakage, and flaring, resulting in substantial economic and environmental costs.

The Quiet Contributors Making Big Impacts

Nitrous oxide (N₂O) might not grab headlines, but it’s 300 times more powerful at warming the planet than carbon dioxide. Agricultural soil management is the largest source of N₂O emissions, primarily from synthetic and organic fertilizers. The irony is palpable: in our quest to feed a growing global population, synthetic nitrogen fertilizer accounts for 2.4% of global emissions, with its supply chain representing 21.5% of annual direct emissions from agriculture.

Recent research shows that nitrous oxide emissions are increasing at a faster rate than any other type of greenhouse gas emission. Nitrous oxide has risen 20% from pre-industrial levels, with emissions from human activities rising by 40% over the past four decades. Nitrogen fertilizers, manure and other agricultural sources drove almost three-quarters of human-caused nitrous oxide emissions in recent years.

Fluorinated gases (F-gases) represent another category that’s small in volume but enormous in impact. These artificial gases can have a warming effect up to 23,000 times stronger than carbon dioxide, with some having atmospheric lifetimes ranging from several years to even centuries. F-gas emissions in the EU have risen by 60% since 1990 while all other greenhouse gases have been reduced. Every time you use air conditioning or refrigeration, you’re connected to this often-overlooked source of emissions, as stationary refrigeration, air conditioning and heat pump equipment are some of the largest sources of F-gas emissions.

When Carbon Sinks Become Carbon Sources

Perhaps one of the most troubling developments in climate science is the transformation of natural carbon sinks into carbon sources. The Amazon rainforest, long considered “the lungs of the Earth,” now presents a stark example of how climate feedbacks can accelerate warming. Parts of the Amazon rainforest are now emitting more than 1.1 billion tons of CO₂ per year, meaning the forest is officially releasing more carbon into the atmosphere than it’s removing.

This shift occurred due to large-scale human disturbances in the Amazon ecosystem, with wildfires – many deliberately set to clear land for agriculture and industry – responsible for most of the CO₂ emissions. The eastern Amazon, which has seen historically greater amounts of deforestation over the past 40 years, has become hotter, drier and more prone to fires. The result is a vicious feedback loop: forest burning produces around three times more CO₂ than the forest absorbs.

The ocean tells a similar story of unintended consequences. The ocean has absorbed about 525 billion tons of CO₂ from the atmosphere since the beginning of the industrial era, presently around 22 million tons per day. While this has helped slow global warming, it has come at the cost of changing ocean chemistry, making seawater 30% more acidic over the past 200 years. Between 1985 and 2024 ocean acidity has increased by 17.5%, but if we go back to the pre-industrial era, this percentage is as high as 40%.

The Arctic Time Bomb

In the Arctic, a massive carbon time bomb lies frozen in permafrost – soil that’s been frozen for thousands of years. Permafrost contains tremendous amounts of carbon, mainly in the form of animal and vegetable matter accumulated in frozen soils over millennia. As global temperatures rise, this permafrost is thawing, and microorganisms break down this matter as soon as the frozen soil begins to thaw, releasing methane and carbon dioxide.

Photo by Mikhail Nilov on Pexels.com

What’s particularly concerning is that rapid thaw processes could potentially increase total emissions by 40% – a factor that has yet to be considered in current climate models. Recent evidence shows that methane emissions for the early summer months of June and July at a permafrost site in the Lena River Delta have increased by roughly 1.9% per year since 2004. However, some research offers a more nuanced view: a study in northern Sweden found that melting permafrost released one tenth as much methane as expected, suggesting that when surface areas dry out after thawing, new plants emerge that help keep methane emissions buried underground.

The Economic Reality of Climate Action

The economics of greenhouse gas emissions reveal both the scale of the challenge and the opportunity. Five national emitters of greenhouse gases caused $6 trillion in global economic losses through warming from 1990 to 2014. Yet the solutions are surprisingly affordable: investing an average of 1.4% of GDP annually could reduce emissions in developing countries by as much as 70% by 2050 and boost resilience.

The relationship between economic growth and emissions is also evolving. The Chinese economy has seen a fourteen-fold growth since 1990, but its CO₂ emissions are five times what they were in 1990. Similarly in India, GDP growth has outpaced CO₂ emissions growth by over 50%. This “decoupling” suggests that economic prosperity doesn’t have to come at the expense of the environment.

Racing Against Time

Perhaps the most sobering aspect of greenhouse gas emissions is how quickly we’re running out of time to address them. The remaining carbon budget for a 50% chance of keeping warming to 1.5°C is around 250 gigatonnes of CO₂ as of January 2023, equal to around six years of current CO₂ emissions. This represents half the budget provided by the 2023 IPCC report.

Yet there are reasons for cautious optimism. The world reached a new milestone as low-carbon sources provided 40.9% of the world’s electricity generation in 2024, passing the 40% mark for the first time since the 1940s.

The story of greenhouse gas emissions is ultimately a story about choices – individual, corporate, and governmental. Every decision we make about how we produce energy, grow food, transport goods, and design our cities ripples through this complex system. Understanding these connections isn’t just about scientific literacy; it’s about recognizing our agency in one of the most important challenges of our time. The greenhouse gases accumulating in our atmosphere today will influence Earth’s climate for decades to come, making every action we take now a vote for the kind of future we want to create.